In recent weeks, producers have focused on soil preparation through plowing and harrowing, as well as sowing Fine Lavender seeds for certain growers. December, however, marks the beginning of the planting season for Lavandin and Clonal Lavender varieties. This critical stage offers an opportunity to delve deeper into the process and assess the current state of the lavender industry.

Planting, a specialized skill for optimal quality

Contrary to popular belief, Lavandin is not grown from seeds but planted. As a sterile natural hybrid, it can only reproduce through cuttings, similar to Clonal Lavenders, which require vegetative propagation. Planting is a meticulous process that demands time and expertise to ensure optimal crop quality in the years to come. Typically starting in December and concluding by early spring.

Planting varies depending on the type of planting material used by producers. It can be done using bare roots, which allow for quick and economical planting but are more prone to drying out. Alternatively, mini-clods, which include a soil clod that protects the roots, can be used. This option facilitates easier establishment after planting but comes at a slightly higher cost and volume. Planting can be carried out in single or multiple rows. The plant density per hectare depends on the variety, while the spacing between rows is determined by the equipment used.

The equipment in question has been developed and improved over the years by producers to suit farms of all sizes and types for their specific needs. Planting is semi-mechanized, requiring manual labor to place the plants one by one into the machine, which then inserts them into the soil. Following this step, the field must be rolled to ensure proper establishment of the plants.

The introduction of inter-row vegetative cover takes place a few weeks after planting. These covers help reduce plant mortality caused by Stolbur decline, a disease transmitted by leafhoppers. Trials conducted over several years by SCA3P have shown that planting a triticale cover in February and removing it at the end of summer during the first two years of cultivation can reduce plant mortality by 50% due to the cover's protective barrier effect.

A Sustainable Planting Approach in a Challenging Market Context

The supply of Lavandin surged between 2019 and 2022, with significant expansion in cultivated areas across various geographic regions. This led to overproduction, which, coupled with declining demand, triggered a deflationary spiral and sales by some operators at extremely low prices—well below the production cost, estimated at over €2,400 per hectare, according to internal data and figures published by CRIEPPAM.

For a medium-sized operation, this translates to a production cost of €24/kg for a yield of 100 kg per hectare, reduced to €22/kg when factoring in subsidies received by producers. This figure excludes equipment depreciation and producer remuneration and is based on a plantation lifespan of seven years, despite the known negative impact of plant decline on productive years. Cultivation costs account for 22% of the production cost, exerting immediate pressure on cash flow. As such, this represents a significant investment for producers.

In this context, it is essential to regulate the expansion of cultivated areas to preserve cash flow and ensure the medium-term survival of operations. Ignoring this market reality and banking on strong future growth would be a risky bet that could harm the entire sector. Controlling the renewal of plantations is crucial to swiftly restoring balance between supply and demand.

A Worrisome Future for Lavandin in Provence

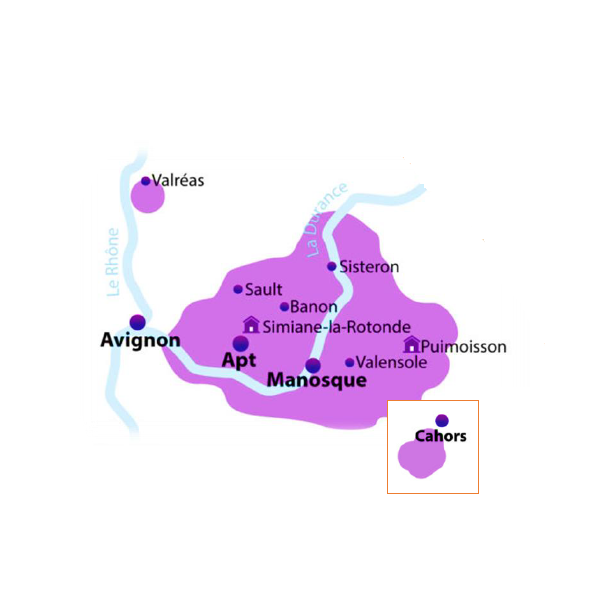

Although overproduction remains a reality due to lower demand, the supply of Lavandin has slightly decreased below 2019 levels, with less than 23,000 hectares currently under cultivation. This decline is largely attributed to widespread uprooting in historical growing regions, averaging a 10% annual reduction over the past two years. The Plateau de Valensole, the heart of lavender production, has seen a significant decline in recent years. Once a flourishing symbol of tourism, the fields of Lavandin are becoming increasingly rare. Technical and economic constraints discourage producers from continuing with this now unprofitable crop, while reduced inputs have impacted the visual appeal of the landscapes.

Renewing part of the plantations is therefore essential to sustainably meet future demand, considering the plant's lifecycle and the technical challenges facing its cultivation. Irregular rainfall caused by climate change, coupled with pest infestations—particularly gall midges—makes it a technically fragile crop. Similarly, the widespread practice of selling at a loss, often through intermediaries, undermines the crop’s social and economic sustainability.

At SCA3P, we advocate for research and the establishment of multi-year contracts that guarantee fair compensation for producers, taking into account both market prices and production costs. These contracts aim to provide a more stable outlook for the future. The goal is to reduce volatility in the long term and break the recurring economic cycles that harm all stakeholders in turn. This year, once again, we have been able to rely on the support of our most loyal partners to strengthen, balance, and sustain commercial relationships.

Planting is not merely a routine step in the agricultural process; it raises many critical questions in the current economic climate and remains a focal point of concern. Rainfall and renewed growth are now hoped for, so that the new plants can thrive under the best possible conditions.